🇮🇪Irish General Election: Three Key Takeaways

Ireland’s general election saw a lot of interest in this year of elections, but what actually happened? and what can we learn from the results?

👋Hey guys, Julien here. The French Dispatch is a reader-supported publication, and both our coverage of current affairs as well as our ability to bring you more news and information on the world around us is entirely funded by paid subscriptions and donations.

If you enjoy reading articles written by high-level experts, then make sure to support the publication by liking, subscribing, and sharing it with your friends and colleagues, and consider taking a paid subscription.

On Friday 8th November, the Irish prime minister, officially called Taoiseach (pronounced ‘Thee-shuck’), Simon Harris of Fine Gael, called a general election for Friday 28th November to elect the 34th Dáil Éireann. Although the official campaign was short, unofficial campaigning began months ago, with the date for the general election the worst kept secret in Ireland.

With a growing population, the number of TDs (MPs) increase from 160 to 174, the highest ever. These are spread across 3 – 5 seat constituencies, growing from 39 to 43. As a country, Ireland has a deep and enduring fondness for the electorally mind-boggling system of Proportional Representation – Single Transferable Vote (PR-STV).

Malta is the only other country to use this system for parliamentary elections, while several legislatures in Australia are elected with PR-STV. The Victorian Electoral Commission has a handy video explaining it.

In terms of the election results, Fianna Fáil and Fine Gael, received a boost in seats, while the Green Party was decimated. Sinn Féin maintained its place as one of the three big parties, with the centre-left Social Democrats and Labour Party making big gains. Finally, right-wing parties such as Independent Ireland and Aontú made smaller increases.

The Irish electorate has spoken, but what have they said? How did the incumbents fair? Where did the grandparents and grandkids place their votes? And did the far-right make a breakthrough? These three key takeaways from the 2024 Irish general election are laid out below.

1. Incumbents were not crucified (except the Greens…)

Since the foundation of the Irish state in December 1922, two centre-right parties have dominated politics: Fianna Fáil (pronounced ‘Fee-nah Fall’) and Fine Gael (‘Fee-nah Gale’). They were born out of a split in an older iteration of present-day Sinn Féin (‘Shin Fey-in’) over the treaty with the UK after the Irish War of Independence (January 1919 – July 1921). Both would become the opposing sides in the subsequent Irish Civil War (June 1922 – May 1923).

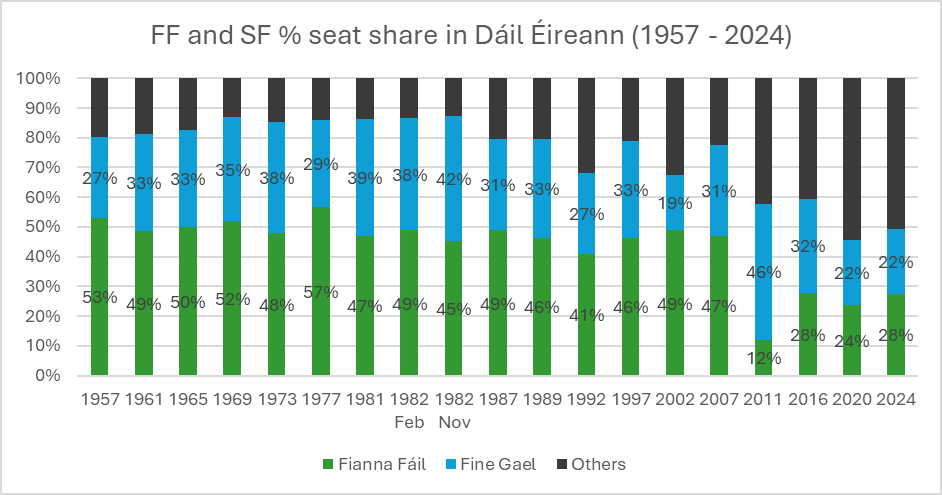

In the decades afterwards, one would either lead the government while the other would lead the opposition. Fianna Fáil led around 70% of all Irish governments between 1922 – 2011. From the late 1950s to the late 1980s, both held over 80% of seats in Dáil Éireann, and as recently as at the November 1982 election, they held 87% of seats.

‘Civil war politics’, as it has been termed in Ireland, unofficially ended in 2016 when Fianna Fáil supported Fine Gael’s minority government. However, it was formally shuttered after the 2020 general election, when both entered government together (with the Greens), with Fine Gael entering government for a record third consecutive time since 2011.

Both centre-right parties went into the 2024 general election attempting the balancing act of trying to distinguish themselves apart in order to entice voters with election promises while defending the record of the government on key policy decisions.

For the 2024 election, I explained here for the French Dispatch the big issues that featured in the campaign, which included a crippling decade-long housing and homelessness crisis.

Despite the two centre-right parties “being in cahoots or coalition” with each other since 2016, the electorate rewarded them with additional seats, with Fianna Fáil now the largest party in Dáil Éireann for the first time since the 2007 election.

Based on first preference votes in the earlier table, it signals that 40% of people in Ireland want a continuation of the political status quo for the next five years. Indeed, the exit poll found that 31% favoured both parties returning into government together without others involved, the largest of such governing options presented in the exit poll.

It is a remarkable outcome considering the pattern of incumbent government parties suffering heavily at general elections across the EU. Fianna Fáil and Fine Gael join the likes of New Democracy in Greece, who are the exception to this current electoral trend and were rewarded by voters come election time.

The same cannot be said, of course, of the Greens, who were left with just one seat. It follows a similar pattern for such parties in other EU countries recently, where their tide of popularity has gone out from under them compared to five years ago. Both Green Party MEPs from Ireland lost their seats at the European Parliament elections in June.

2. A generational divide

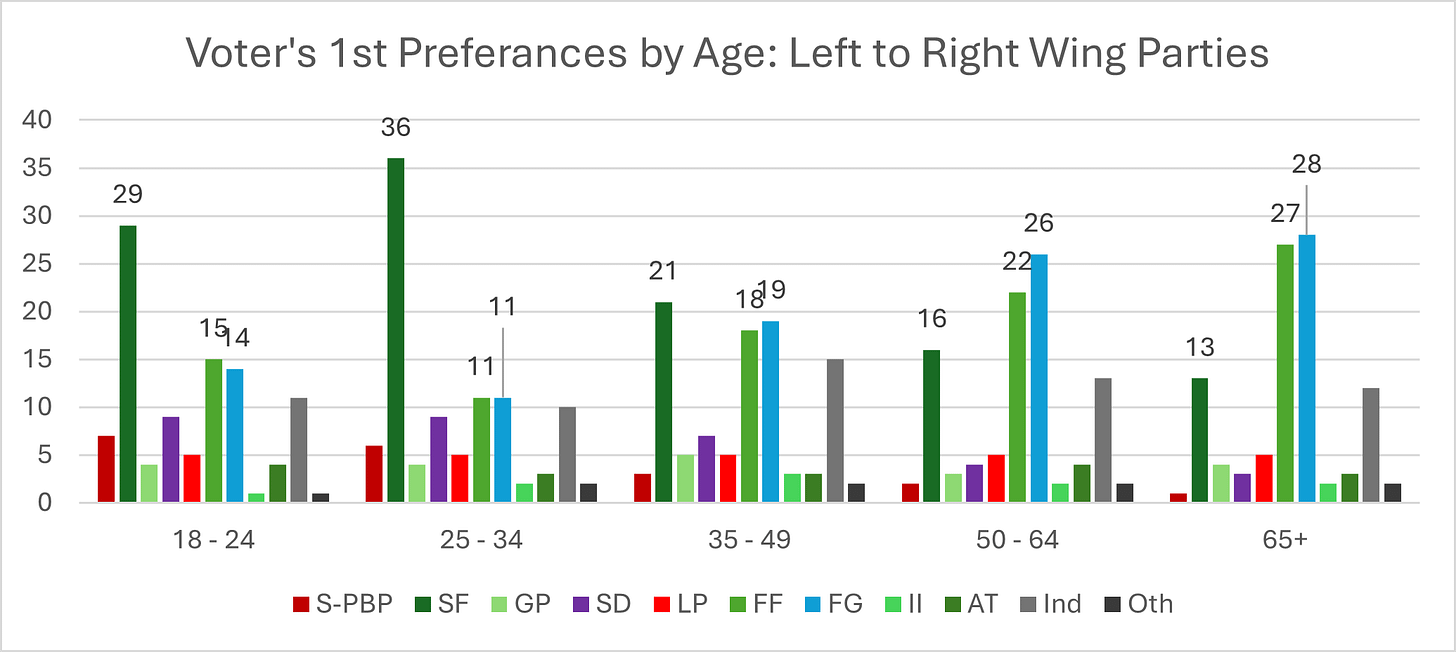

A very clear generational divide now exists between younger and older voters on who they gave their first preference to. As the graph below highlights, the exit poll found that Sinn Féin was the largest party for those aged 18 – 24 (29%) and 25 – 34 (36%), after which the numbers dip when looking at older age groups. Please see the graph below.

A source of this appeal to younger voters for Sinn Féin was its campaign message of change and an opportunity to have, for the first time ever, a government not led by Fianna Fáil or Fine Gael. A left-wing nationalist party, its anti-establishment rhetoric appealed to younger voters during the 2010s on issues such as the housing crisis.

As a result, it has been able to broaden its base beyond working-class urban areas and along rural areas of the border with Northern Ireland.

For Fianna Fáil and Fine Gael, their support grows as we move up through those older age groups, in particular those aged 50 – 64 and 65+. Throughout the election, they were able to highlight their record of managing the economy successfully, from the painful years of the EU – IMF bailout to shepherding it through the recent crises such as COVID-19.

In short, younger voters who feel that the two establishment parties are not solving their pressing needs, in particular housing, look towards Sinn Féin for a change in the political status quo. Meanwhile, older voters broadly see Fianna Fáil and Fine Gael as the responsible, steady hand at the tiller to manage Ireland’s economy.

3. No right-wing breakthrough

While right-wing parties such as the Aontú (‘A-in-two’) and the newly established Independent Ireland made marginal increases in seats in Dáil Éireann, there was no breakthrough of the far-right. Such parties received very few first preferences, such as the Irish Freedom Party (0.6%), The Irish People (0.3%), the National Party (0.3%), or Irish First (0.1%).

Due to the significant recent increase in refugees coming into Ireland, it has been exploited by far-right parties and groups, pulling immigration into being politicised for the very first time in Ireland. This all boiled over onto the streets of Dublin city centre in November 2023, as the country was shocked as it witnessed a rare occurrence of violent riots.

However, when looking at the most important issue for voters in the general election were, immigration came fourth in the exit poll at 6%. The clear top issue was housing and homelessness at 29%, followed by the cost of living at 19%.

Although, at present, Ireland’s far-right presence remains on the political margins, Ireland is not immune to the rise of the far-right, and it remains to be seen over the coming years what their trajectory will be here.

What of government formation?

A new government will not be in place before Christmas, and it looks like government formation talks could last until well into January and possibly into February.

It is widely expected that Fianna Fáil and Fine Gael will enter government together for the second time. However, they are just short of a working majority, and with the Green Party no longer a viable coalition option, they have to look elsewhere.

It is not the first time in Irish coalition government history that the smaller party has been decimated after an election. It has given pause for thought for the Social Democrats and the Labour Party in terms of entering government.

The Labour Party looks to have been forgiven by the electorate for being in government with Fine Gael between 2011 – 2016, during the painful years of austerity. Meanwhile, the Social Democrats returned their highest number of seats since being founded in 2015. Both will likely wish to maintain their electoral gains and not end up like the Green Party.

The most likely outcome is that a number of independents will be approached and enticed with bilateral agreements that will benefit their constituencies. This was done for the 2016 – 2020 Fine Gael minority government, which remained stable and served its full term.

And people will indeed be looking for stability as Ireland and the EU brace for a challenging 2025 and beyond.

Ciaran O’Driscoll researches EU politics.

Thank you for reading the French Dispatch! If you liked what you read, you should like this post and subscribe to the newsletter by clicking/tapping the button below:

And if you’d like to contribute a coffee or two to help fuel my coverage of the wild world of politics, feel free to click on the picture below:

For some, the election results come down to electing the devils you know (FF and FG), at least for the older age groups. In that age range the memories of Sinn Fein's involvement with the havoc of IRA activities during the Troubles are still strong. But SF has a viable claim of being the only real all-island party, and demographics seem to be on its side. Housing and Cost of living are oppressive issues; I was only surprised to see not more concern about direction of the Health Services Executive and healthcare generally.